Animals chase themselves to escape predators

To escape the attack of crabs, a sea slug is ready to cut off the paddle-like fins in the back to swim away.

Scientists from Victoria University, Canada, argue that the process of autopsy of the nudibranchs named Melibe leonine is a way to prevent predators from attacking vulnerable parts of the body. The discovery was published by the team at the annual meeting of the American Biological Society in Portland, Oregon on January 4.

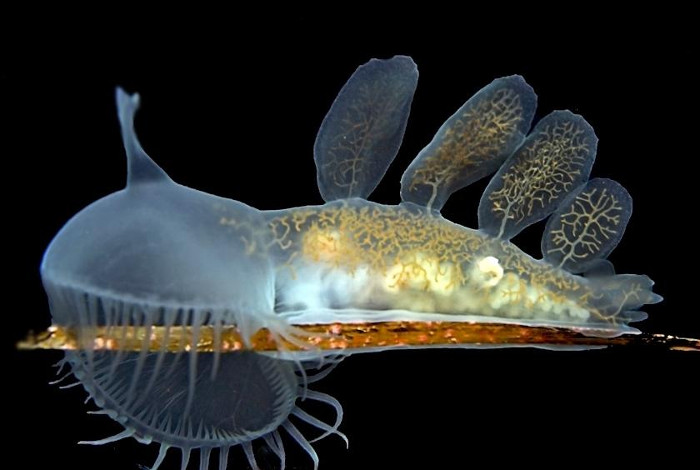

According to Nature World News, the sea slug Melibe leonine does not have a protective shell. This mollusc species lives on seaweed plants and uses a hat-shaped mouth with many tentacles to catch small plankton shrimp. At the back of the body they grow out of the cerata fins with detached ability.

Sea slug Melibe leonine is capable of self-limbs.(Photo: Tumblr).

When being attacked by sea crabs, grabbing these fins, the sea slug Melibe leonine uses a very unique escape strategy.

"In a dangerous situation, the tissue of cerata's root disintegrates, causing the fin to fall," explained Louise Page, a researcher at Victoria University. This passage is similar to the way the lizard cuts its tail when caught by predators. Sea slugs can regrow the broken fin afterwards.

"The limb is the process of removing the appendage itself, and the animal must have a way to heal the wound so that it does not bleed to death," Page said.

In the new study, Page looked at the area at the base of cerata and discovered some unique features such as small granular cells directly connected to nerves.

After that, Page's group explored the signals that trigger the process of self-passage. According to them, when this mechanism takes place, the vertical muscles contract, causing pressure on the base of the fin, releasing particulate matter from the cell and breaking the connective tissue. Two two sphincter muscles along the base of the fins shrink to separate the cerata and heal the wound, helping the sea slug to die. The findings could lead to a breakthrough in medicine for treating patients' wounds.

- 'Stealthy' predators in India

- Great hot escape of animals in the desert

- New Zealand will kill all predators

- Insects disguise as predators to escape

- Messages from animal colors

- Explaining the phenomenon of the hideous Pig in Cannock Chase forest

- The bigger the brain, the better the reflex ability of predators

- Kangaroo roars with wild dogs

- This great invention is the solution to save hundreds of people in the sea of fire

- Fearful cats flee the mouse on the street

- Lions, tigers escape from the zoo after the great flood

- Tag the hunting animals in the Pacific

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend

Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast

A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast Compare the size of shark species in the world

Compare the size of shark species in the world