The truth of the death of the 16th century astronomy

Two years after the body of Tycho Brahe was unearthed at the tomb in Prague, chemical analyzes showed that this 16th-century astronomer did not have to die of mercury poisoning or assassination as rumors, which can be reaffirmed that he died of bladder rupture.

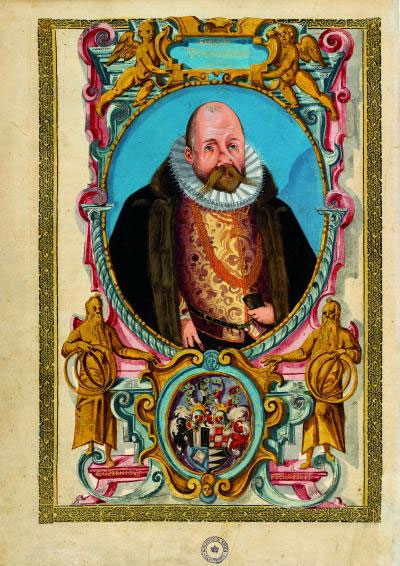

Brahe was born in Denmark in 1546. He served Danish kings as an astronomer before settling in Prague during the Roman Emperor Rudolph II.

He is known for being able to make the most accurate measurements of stars and planets without the aid of a telescope, and he can prove comets to be objects in space and not in the atmosphere of the earth. Assistant to Brahe is the famous German astronomer Johannes Kepler.

Brahe's beard and tooth analysis showed that he did not

died of mercury poisoning.(Photo: Livescience)

A long time ago it was discovered, Brahe died of a bladder infection after he used the royal bathroom in October 1601 and broke his bladder. To celebrate 300 years of Brahe's birth, scientists opened his grave in 1901. This time Brahe's death was declared due to mercury poisoning, sparking rumors of this talented astronomer. has been poisoned. Some even accused Kepler of jealousy, so he went down with Brahe.

However, the new analysis results do not see any assassination plot for Brahe. Through an initial analysis of the teeth, Brahe's Danish and Czech researchers examined the bones and whiskers, saying the mercury levels in his body were not high enough to kill Brahe.

Even the test of beard revealed that the level of mercury also dropped to a level lower than normal in the weeks leading up to his conclusion.'In fact, bone chemistry analysis showed that Tycho Brahe was not exposed to unusually high levels of mercury in the last 5-10 years , ' said researcher Kaare Lund Rasmussen, a chemistry professor at The University of Southern Denmark said.

Especially, the test also revealed Brahe's famous silver fake nose was actually made of brass. Evidence of green stains around Brahe's area of the corpse of the corpse contain copper and zinc traces. By examining small bone samples from the nose, Brahe's artificial nose was not made of precious metal as previously speculated, said Jens Vellev, an archaeologist at Aarhus University in Denmark. Now scientists have taken CT images of Brahe remains and hope to restore his image.

- Mexico discovered 16th-century Mayan tombs

- Compare 16th century maps and satellite maps today

- The aromatic oil of the aristocratic family of the 16th century French

- Radio astronomy and giant antennas

- The skeleton of the 16th century was stuffed with vampire bricks?

- The truth is hard to believe: A pair of experimental mice can be as expensive as a billion-dollar car

- The origin and characteristics of African lion dogs

- The house fly - voracious, dirty

- Near-death experience through the insights of insiders

- The truth is

- The mysterious 19th-century shipwreck: What terrible thing happened to the members on board?

- Discover a rare American map

The truth about the mysterious red-haired giant at Lovelock Cave

The truth about the mysterious red-haired giant at Lovelock Cave Inunaki Tunnel: The haunted road leading into Japan's 'village of death'

Inunaki Tunnel: The haunted road leading into Japan's 'village of death' The mystery of the phenomenon of human reflection before dying

The mystery of the phenomenon of human reflection before dying 6 mysterious phenomena, although science has been developed for a long time, still cannot be answered

6 mysterious phenomena, although science has been developed for a long time, still cannot be answered