Decipher the mysteries of the space rock of the past 50 years

Scientists may have finally come up with an explanation for one of the oldest mysteries of the Apollo program: why some rocks brought back from the Moon's surface appear to have formed inside. a strong magnetic field like on Earth.

The moon does not have a strong magnetic field

Scientists believe the Moon's interior cooled fairly quickly and evenly after it formed about 4.5 billion years ago, meaning it doesn't have a strong magnetic field - and many scientists believe this that never happened.

How then, some of the 3-billion-year-old rocks recovered during NASA's 1968 to 1972 Apollo missions look like they were created inside a geomagnetic field strong enough to compete with Earth's? earth, while the others barely have any magnetic imprints?

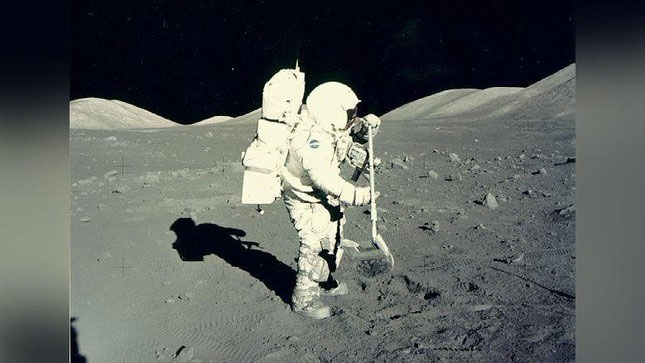

Astronauts on the Appolo 17 spacecraft stepped down to the surface of the Moon and used a rake to excavate soil and rocks.

Alexander Evans, a planetary scientist at Brown University, said: "Everything we've thought about how the magnetic field is generated by the planetary core tells us that an object the size of the Sun is. The moon wouldn't be able to create a field as strong as the Earth's."

Scientists have come up with a range of potential explanations over the past 50 years for this strange discrepancy.

Perhaps, after its formation, the Moon did not freeze as quickly as initially thought; or maybe the Moon's gravitational interaction with Earth causes it to magnify oscillations, swaying around in the cooling interior to increase its magnetic field.

Moon core launch collisions

Another opinion is that, as asteroids bombarded the Moon so much, the collisions kicked off the Moon's core into proper activity.

Now, Evans and co-author Sonia Tikoo-Schantz, a geophysicist at Stanford University, have come up with an entirely new explanation, published in the January 13 issue of Nature Astronomy.

"Instead of thinking about how to power a strong magnetic field continuously for billions of years, there might be a way to create a discontinuous high-intensity field," says Evans.

During the first few billion years of the Moon's life, long before most of it froze inside, leaving only a small iron inner core surrounded by a molten outer core, the orbiting companion Ours is an ocean of molten rock.

Crucially, however, the Moon's core is not significantly hotter than the mantle above it, meaning very little convection between the two Moons occurs. The fact is, the Moon's molten substances cannot mix inside it, meaning it cannot have a stable magnetic field like the Earth's.

The moon creates a strong intermittent field

But, the researchers say, the Moon may have created a strong intermittent field. As the Moon cools over time, the minerals contained within its hot magma cool at different rates. The densest minerals - olivine and pyroxene - will cool and sink first, while the less dense magma, containing titanium along with thermogenic elements such as potassium, thorium and uranium, will rise just below the crust and heat loss then on.

Once cooled to the point of crystallization, the titanium-containing rock will be much heavier than the solids below, causing it to sink slowly but inevitably toward the molten outer core.

By studying the known composition of the Moon and making a calculated guess about its past mantle viscosity - or how easily its magma might have stirred - scientists estimate calculated that the titanium sunk on the moon would break up into small clumps 37 miles (60 km) across and sink at various rates in about a billion years.

Every time one of these chunks of cold titanium hits the Moon's hot outer core, the temperature difference reactivates the core's dormant convection currents, briefly kicking off the Moon's magnetic field. .

If the Moon's magnetosphere is indeed so unstable, these brief outbursts of magnetism would suffice to explain why different rocks found on the Moon carry different magnetic symbols. together.

- Mysterious cut bisects rocks over 10,000 years old in Saudi Arabia

- Decipher the mysterious language of dolphins

- 12 mysteries that science cannot find an explanation

- Great discoveries about the universe are unknown (1)

- Gamers decipher scientific mysteries

- Why did NASA bring so many Moon rocks but almost did not touch them?

- NASA built WFIRST wide-angle telescopes, hunting life out of Earth

- Despite the laws of physics, the 500-ton rock keeps hanging in the air - The experts are also helpless!

- Particle counting machine on the International Space Station

- The discovery of a rock planet is very similar to the globe

- The rock resembles pork over 100 million years old

- 12 'super fun' facts that amaze you

Van Allen's belt and evidence that the Apollo 11 mission to the Moon was myth

Van Allen's belt and evidence that the Apollo 11 mission to the Moon was myth The levels of civilization in the universe (Kardashev scale)

The levels of civilization in the universe (Kardashev scale) Today Mars, the sun and the Earth are aligned

Today Mars, the sun and the Earth are aligned The Amazon owner announced a secret plan to build a space base for thousands of people

The Amazon owner announced a secret plan to build a space base for thousands of people