Decoding the custom of self-immolation following one's husband in India

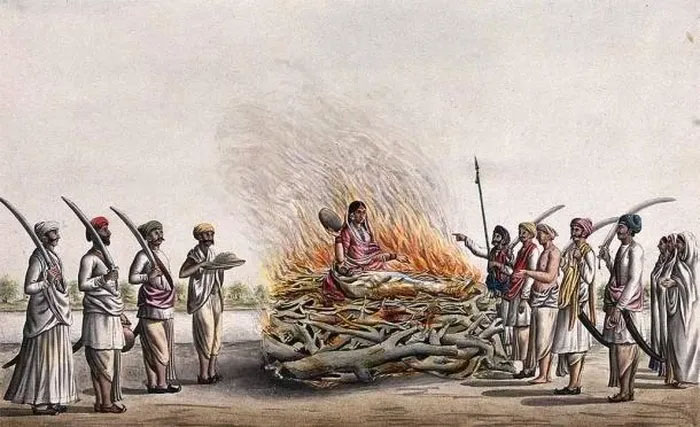

If we were to choose the most controversial custom in South Asian culture, then Sati - the self-immolation of India to follow her husband to death - would certainly be at the top .

Because on the one hand, it is an act of absolute loyalty and on the other hand, it shows extreme male prejudice, so tyrannical that it even takes away the life of the already pitiful widow.

Origin and abuse

Widows who do not voluntarily commit Sati will be forced to do so. (Illustration: Ancient-origins.net).

Sati is a Hindu religious practice named after Goddess Sati. Hindu mythology tells that Sati was a goddess who disobeyed her father to marry Lord Shiva. Because her father despised her husband, in a fit of anger, she burned herself to death in protest and before entering the fire, she prayed to be the wife of Lord Shiva in the next life.

Her prayer was answered and she was reborn as Parvati to continue her marriage to Lord Shiva. Hindus admired Sati's loyalty and followed her in her self-immolation. When her husband died, his wife would not remain a widow but would voluntarily follow him to the afterlife to continue their married life.

The date of the practice of Sati is still uncertain but the earliest record of it is probably from the 4th century BC . The venerable Greek historian, Aristobulus of Cassandreia (375 - 301 BC), during his trip to India with Alexander the Great (356 - 323 BC) in 327 BC, recounted the practice. Other historians of the time such as Cicero, Nicolaus of Damascus, Diodorus… also left similar records.

According to historians, initially, Sati was only practiced in some regions because in addition to the above historians, other historians who visited India did not mention this custom. It was not until around 400-500 AD that it became popular and from 1000 onwards, it dominated the entire religious life of India.

Indian society was divided into four classes, Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (nobles, warriors), Vaishyas (craftsmen, merchants, farmers) and Shudras (slaves). The first class to practice Sati was probably the Kshatriyas and they performed it as an example to the laity.

Some historians also believe that Sati was combined with Jauhar, the practice of suicide to maintain dignity and chastity of upper-class women. Because of its combination with Jauhar, the act of immolating oneself to follow one's husband also changed its meaning, from 'a courageous act' to 'a virtuous act' and 'an act to be done'.

Under the meaning of 'action to be done', Sati has both shades: Voluntary and forced . If the widow does not voluntarily burn herself to death to follow her husband, she will be forced by society to burn herself. There are many methods of Sati but the most common is that the widow sits or lies next to her husband's body on the pyre, accepting to be burned to death.

Decay and not death

Today, Sati still quietly occupies a corner of Indian spirituality and life. (Illustration: Reddit.com).

Unlike the flowery religious reasons, the real cause of Sati is very bitter. In Hindu society, women are not given any role or status and are considered a burden.

Because they did not want to be known as abandoning them, Sati appeared, solving the problem in the most direct and radical way. Usually, widows who had to practice Sati were those who did not have children. Sati had a principle that prohibited widows who were pregnant or taking care of young children from practicing it. It also exempted women from the upper class.

The first person to see the cruelty of Sati and want to end it was Akbar the Great (1542 – 1605), the third Mughal emperor (1526 – 1857). He respected the willingness of women to follow their husbands to the afterlife, but he opposed self-immolation, feeling that it was an improper way to show loyalty. In 1582, Akbar banned Sati.

Although Sati was banned, Emperor Akbar did not go so far as to enforce it. It was not until 1663, under the direction of Emperor Aurangzeb (1618 - 1707), that Sati was actually banned. In the eyes of the Indian colonial powers, Sati was also an evil practice and they tried to end it.

In 1798, the British banned it but it was only effective in the Calcutta area. In the early 19th century, in an effort to convert Indians, they mobilized many campaigns to ban Sati but encountered unexpected negative effects. From 1815 to 1818, the number of Sati cases suddenly doubled. The reason was that Hindus abused it to express their opposition to conversion.

In 1828, the newly appointed Governor of India, Lord Willian Bentinck (1774 – 1839) firmly imposed the law prohibiting Sati, punishing individuals and groups who committed it with imprisonment. Sati decreased but did not die out completely and was still 'turned a blind eye' in many regions. It was not until 1861 that the law prohibiting Sati came into effect throughout India.

In 1947, India regained its independence. Since then, both the government and the people have opposed Sati but, in 1987, Roop Kanwar, an 18-year-old widow from Deorala village, was forced to commit Sati along with her 24-year-old husband.

Thousands of people gathered to watch and praise, causing public opinion in India to explode with anger. The Indian government had to issue a Sati Prevention Ordinance, then quickly passed a new Sati prohibition law, imposing maximum penalties of life imprisonment and death.

Despite the laws and propaganda, raising the awareness of the people, Sati still takes root in a corner of the Indian spirituality. Occasionally, it is practiced and as long as there is no investigation and coercion, the law cannot be enforced.

In the 17th century, a French traveler named Jean Baptiste Tavernier visited India and reported seeing people build a small hut, carry the husband's body and the widow inside, close the door, and then burn it. Some other travelers reported seeing people dig a pit, fill it with flammable materials, place the husband's body, lower the widow into it, and set it on fire. Both the hut and the pit served the same purpose: to prevent the widow from running away, interrupting the Sati ritual. In addition, the widow was allowed to drink poison, let herself be bitten by a poisonous snake, or commit suicide by knife.

- Cold nape with the custom of burning his wife to ... show respect for her husband

- 32 people set themselves on fire to set a world record

- Husband is worried because he understands his wife

- Family is easy to melt if the husband is happier than his wife

- Thanksgiving custom is different throughout the five continents

- Decoding DNA of malaria parasite

- Interesting little facts about India

- The custom of Christmas in the devil costume

- Wife was beaten by her husband and still happy

- Funny poetry for old husband lazy bathing

- The legend of Mr. Apple

- New discovery about the custom of burial in the ice age

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why?

The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why? History of the iron

History of the iron What is alum?

What is alum?