Gene editing to select sex for animals to reduce killing

Scientists have used gene-editing technology to create litters of all-female or male mice and are targeting chickens to prevent indiscriminate killing.

This technique is ushering in a new era for the livestock industry that could prevent the mass destruction of unwanted, costly or unproductive males.

Mice have been genetically modified to produce only male or female offspring for scientific research.

Initially, scientists in the UK chose to create the desired sex by gene editing techniques in mice used in the studies. The team say they are moving towards a trial of the chicken industry that could help prevent the slaughter of millions of innocent male chicks in the UK from being culled simply because they. don't lay eggs.

Currently, the British government is considering to move towards licensing gene editing to be used for the domestic livestock industry.

The new technique, published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, enables the disabling of a gene involved in embryonic development. The system can be programmed to activate male or female embryos at the very first stage of the embryo, which has just formed between 16 and 32 cells.

The researchers believe the technique could be widely used in protein-producing animals, and they are in discussions with the Roslin Institute to set up pilot studies, a world-first, ground-breaking move. on livestock gene editing.

Dr Peter Ellis of the University of Kent said that, if the results were allowed to move from the laboratory to commercial application, they could have "far-reaching" effects on animal welfare.

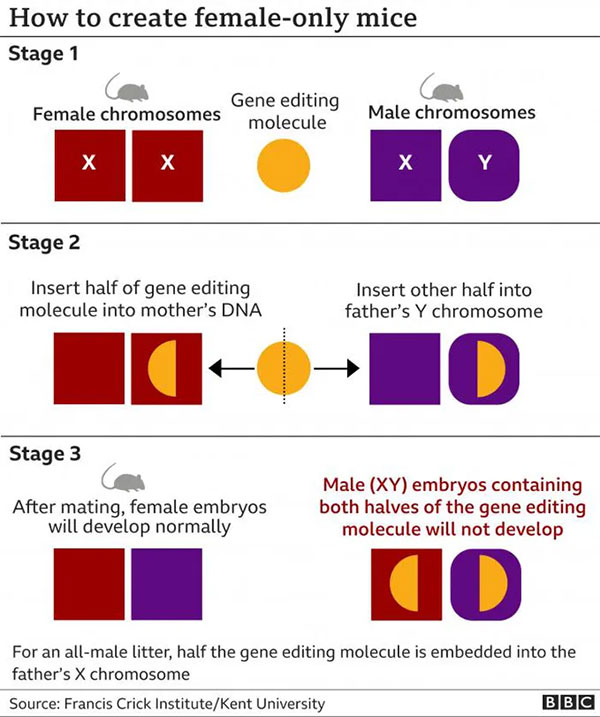

Diagram depicting the stages of research to create mouse offspring with the desired sex of humans.

"It is estimated that between four and six billion chicks in the poultry industry are killed each year worldwide. In principle, we could set up a system so that instead of mass culling of chicks, we could have After they have just hatched, they have suffered and died miserably, these eggs are simply not put into the incubator," said Peter.

Dr James Turner, of the Francis Crick Institute in London, compiled a list of 25,000 scientific research reports published in the past five years that required male or female mice separately. "The number of mice used in each particular case varies, but often runs into the hundreds of thousands. This sex-selection gene-editing technique has had an immediate impact and is very valuable in clinical trials. science lab," said James.

An independent report published earlier this week said animal welfare should be at the heart of any relaxation of laws allowing gene editing on farm animals.

One of the report's authors, Mr. Peter Stevenson, a leading policy adviser at Compassion in World Farming, said he was "cautious/wary" of the situation. gene editing in general, as it can be abused to manipulate/manipulate livestock and poultry production facilities. However, he strongly welcomes its applicability to sex selection in chickens.

"We advocate using it to improve animal welfare, such as ensuring that hens produce only female chicks, as this will prevent the killing of millions of unwanted chicks. in the UK every year".

Barney Reed of the charity RSPCA says the technology must be strictly regulated. "This is especially relevant when many of the potential 'benefits' touted are to address human-made environmental or animal welfare problems," he said.

Dr. Ellis agrees, saying: "Any potential use in agriculture will require extensive dialogue and debate, as well as legislative changes. Scientifically More research is needed, first to develop gene-editing toolkits specific to different species, and then to test whether they are safe and effective. fruit or not," said Dr. Ellis.

How does it operate?

Whether a mammal is male or female is determined by sex chromosomes. Children have one pair of X chromosomes - one inherited from the mother and one inherited from the father. However, males (males) have one X chromosome from the mother and one Y chromosome from the father.

The chicken industry will probably be the first to apply.

With this principle in place, the researchers were able to stop XX or XY mouse embryos from developing by disabling a gene, resulting in embryos progressing at a very early stage with about 16 to 32 cells. cell.

They were able to select sex by embedding half of a gene-editing molecule, called Crispr-Cas9, which disables genes into the mother's DNA and the other into the father's X or Y chromosome , depending on the requested sex.

Genes can only be disabled if both parts of Crispr-Cas9 are combined. If half of the father's gene-editing molecule is located on the male's Y chromosome, once it fuses with the maternal DNA containing the other half-editing molecule, the resulting male XY embryo will have both parts of the gene. molecules that disable genes, preventing further growth. But all female embryos, which have not inherited the molecule from their father, develop normally. For an all-male litter, half of Crispr-Cas9 is embedded in the father's X chromosome.

- The world's first human genome

- The unpredictable harm from Chinese scientists' genetic modification experiment

- US gene editing albino lizard

- Research and develop gene editing technology with US soldiers

- Create 'pencil' for genetic errors

- The statement by the Chinese scientist about genetically modified children is disgusting

- For the first time in history, the aging process can be reversed, helping young people never grow old

- The project helps you to edit your own DNA at home

- The first time the CRISPR gene editing process is back

- Editing genes can lose geniuses

- For the first time, three cancer patients in the US were treated with CRISPR gene editing technology

- The study predicted that two girls who had their genes altered would die soon after they were withdrawn, the results unreliable

'Barefoot engineer' invents a pipeless pump

'Barefoot engineer' invents a pipeless pump Process of handling dead pigs due to disease

Process of handling dead pigs due to disease Radiometer

Radiometer Warp Engine: Technology brings us closer to the speed of light

Warp Engine: Technology brings us closer to the speed of light