After 170 years of industrialization, humans have broken a law that has existed for billions of years in the ocean

When humans dominated the oceans, we defeated the top predators to sit at the top of the food chain. All the fish and seafood that we catch is only serving only 3% of human food needs. But it was equivalent to 2.7 billion tons of the largest living species.

When it comes to life on Earth, we often assume it's the pure domain of biologists. The study of life does not seem to share laws with the physical world or formulas with the mathematical world. But the truth is not so.

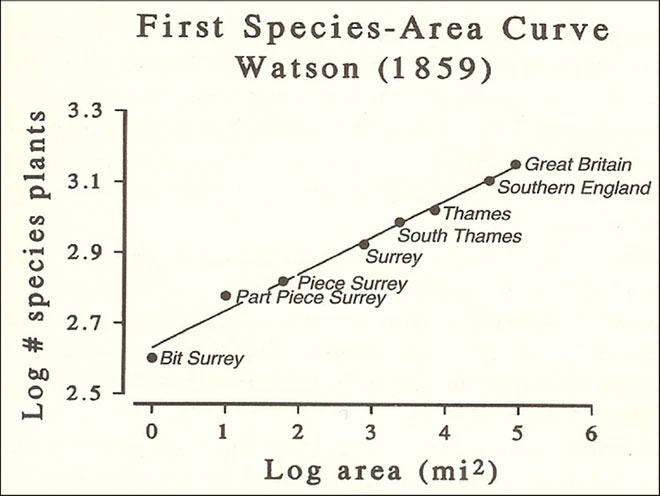

When God created animals, "he" secretly introduced into them the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The diversity of plant species follows an exponential function proportional to the area occupied by those plants:

This chart, drawn from 1859, shows the number of different plant species found as their habitats were extended from a small county in England to an entire island nation. All are exponential.

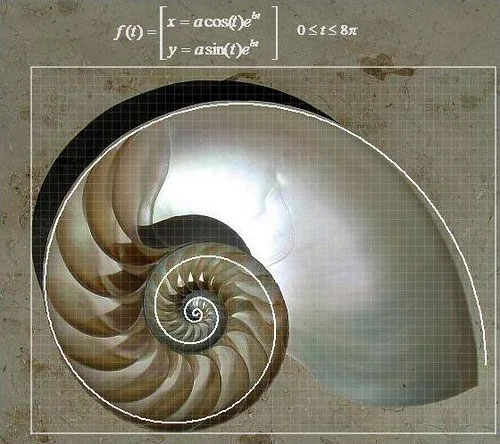

It can be seen that the exponential or power function is a favorite formula of nature. It appears in the spectrum of the size and frequency distribution of eruptions on the surface of the Sun, the number of craters on the Moon, the size of neurons in the human brain.

The spirals of galaxies, the shells of snails, and the flowers of plants all grow exponentially with a logarithmic helix. The same is true of every structure from the horns, teeth, spines, scales, claws and beaks of animals.

Vortex of the galaxy.

Structure of a snail shell.

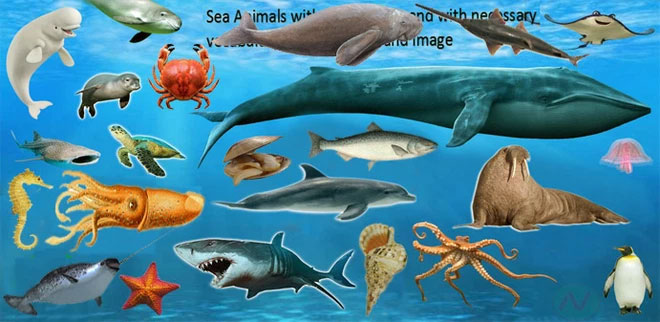

In the ocean, nature also establishes an exponential function called the "Sheldon spectrum", which determines the size and number of marine species. The Sheldon spectrum may have existed for billions of years since the first creatures appeared in the ocean.

But in the last 170 years, as humans industrialize the oceans, the Sheldon spectrum has rapidly broken down.

The Sheldon spectrum: How nature distributes life in the oceans

The Sheldon spectrum was first proposed by Canadian marine biologist Raymond W. Sheldon in 1972. After statistical studies he carried out in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, Sheldon discovered the biomass density of The marine ecosystem is a logarithmic function that is approximately constant over many orders of magnitude of the organism.

To put it simply, the larger the size of sea creatures, the fewer their individuals in the ocean will be. According to Sheldon, this ratio follows an exponential constant for all living things of all sizes, from bacteria to whales.

For example, molluscs that are 12 orders of magnitude smaller than tuna (about 1 billion times) will also have a population 12 orders of magnitude more than tuna, or 1 billion times.

The result of the Sheldon spectrum is that it makes the biomass of species in the ocean almost similar. That is, if you catch all the tuna in the world and weigh it, the kilos you get are the same as the kilos of krill that are in the ocean.

This has been tested in a number of small environments, where scientists have found that the Sheldon spectrum holds true for a wide range of cases, from marine plankton to freshwater fish.

The Sheldon spectrum holds true for so many cases, from marine plankton to freshwater fish.

The study showed that the biomass of organisms in the ocean bed complied with the exponential of the Sheldon spectrum.

But in a new study for the first time, scientists from Germany's Max Planck Institute want to expand the scope and test the Sheldon spectrum on a global scale. The goal is to see if it holds true for all oceans.

To do that, they surveyed 33,000 sites, 12 groups of organisms that range from bacteria, algae, zooplankton, fish to mammals like dolphins and whales, around the globe.

"We've made estimates for organisms from the smallest level, in more than 200,000 water samples collected worldwide," said ecologist Ian Hatton from the Max Planck Institute. "The mass ratio of these organisms is comparable to that between humans and the entire Earth."

According to Hatton, the biggest challenge the team faced was synchronizing the estimates to compare the biomass of different size species, from bacteria to whales. Each sea creature requires a different estimate, so synchronizing them is difficult.

The ocean was perfectly balanced in pre-industrial times, until it was taken over by humans

Overcoming technical and methodological challenges, Hatton and his team finally got their results. It confirmed the Sheldon spectrum to be true to historical data and to the conditions of a pre-industrial ocean, that is, before 1850.

"We were surprised to see that each trophic level has a biomass of about 1 gigaton globally," said geologist Eric Galbraith from McGill University. "The fact that the sea creatures were evenly distributed across all sizes is remarkable."

According to Galbraith, nature could have arranged life in the ocean in many ways. For example, why doesn't God favor a medium sized but highly intelligent creature in the middle of the Sheldon spectrum? For example, if dolphins really have human-like intelligence, they can also grow with tremendous biomass to dominate the ocean.

Hatton and his team at the Max Plank Institute discussed these questions. According to the study, there are many factors in the seabed that can maintain the Sheldon spectrum, including interactions between predators and their prey, metabolism, growth, reproduction and mortality rates. .

In the opposite direction, Hatton found one factor that could disrupt that balance: people. After comparing pre-industrial statistics with today's marine biomass, the scientists noticed a sharp drop in fish species on the right side of the Sheldon spectrum.

"Human impacts appear to have significantly truncated the tail end of the spectrum," the team wrote. That is explained by the introduction of ocean-going fishing vessels in the industrial era, which greatly increased our fishing productivity. Coupled with that is population growth on a global scale, which requires a larger amount of seafood to feed us.

"Humans have not only come and become the top predators in the ocean, but we have fundamentally changed the flow of energy through the ecosystem, through the impacts that we accumulate. over the past two centuries," the study said.

Since the 1800s, we have lost 60% of the biomass of fish and marine mammals. This is even worse for giant creatures like whales. Historical whaling has reduced their numbers by as much as 90%.

Some species such as the blue whale have disappeared by as much as 99% in the period between 1900 and 1960 alone. Humans have wiped out 1.5 million whales in Antarctic waters alone, contributing to what called the "paradox of the mollusks".

The decrease in biomass of fish and marine animals due to human exploitation began with the industrialization period.

"It looks like we've broken the Sheldon spectrum, one of the biggest known in nature," said marine ecologist Ryan Heneghan from the Queensland University of Technology. "And humans aren't just catching fish, we're impacting the oceans in an unimaginable way."

All the fish and seafood that we catch is only serving only 3% of human food needs. But it was equivalent to 2.7 billion tons of the largest living species in the ocean.

The researchers suggest that with these numbers, the fishing industry should reintroduce its operations. "We can reverse the imbalance we have created by reducing the number of fishing vessels operating around the world," they wrote. "Reducing overfishing also helps develop more sustainable fisheries. That would be a win-win."

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.

- Industrialization ends the Little Ice Age in the Alps

- Photos of Anthropocene: How do people devastate the Earth?

- American farmers find meteorites billions of years old

- Decomposing ocean plastic produces toxic chemicals

- Learn about the existence of billions of birds

- Humans and sharks have the same ancestors

- Billions of alien civilizations have existed

- Technology can provide enough energy for humans for billions of years

- The 300-year-old password was broken

- The temperature of the oceans billions of years ago is not hotter than today

- Discover an oasis of more than 3.5 billion years on Mars once had life?

- Circles around Saturn are billions of years ago

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend

Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast

A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast Compare the size of shark species in the world

Compare the size of shark species in the world