CrCoNi Alloy - The Hardest Material on Earth

Scientists studied an alloy made of chromium, cobalt and nickel (CrCoNi) and measured the highest hardness of any material .

Not only is the CrCoNi alloy ductile, its strength increases as it cools, unlike most metals. The team, led by researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, published their breakthrough in the journal Science on December 2. "When you design building materials, they need to be strong, ductile, and resistant to breaking," said Easo George, co-leader of the project. "Usually, those properties cancel each other out. But this material has it all. Instead of becoming brittle at low temperatures, it becomes stronger."

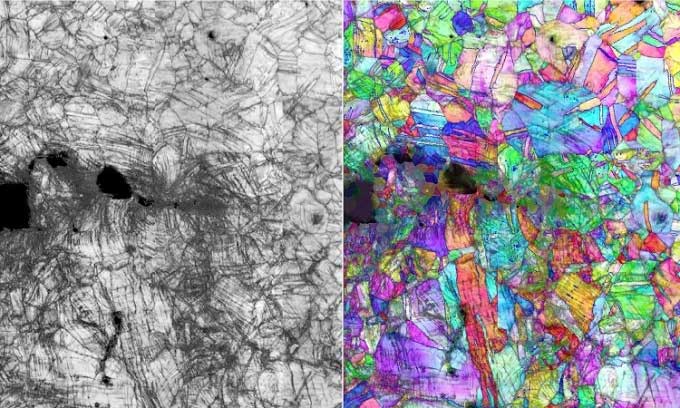

The crystal structure of CrCoNi seen under a microscope. (Image: Berkeley Lab)

CrCoNi is a subgroup of metals called high entropy alloys (HEAs) . All alloys in use today contain large amounts of one element and smaller amounts of other elements, but HEAs have the same mass of all the constituent elements. This balance results in high strength and ductility under pressure.

The new material's stiffness near liquid helium temperature (-253 degrees Celsius) is as high as 500 MPa-Sqrt (a measure of stiffness) . For comparison, silicon has a stiffness of 1, the aluminum frame of a passenger jet is 35, and some of the best steels are around 100. So 500 is an incredible number, says study co-leader Robert Ritchie, a scientist in Berkeley Lab's Materials Science Division.

The team began experimenting with CrCoNi and another alloy that adds manganese and iron (CrMnFeCoNi) nearly a decade ago. They made samples of the alloys, then cooled them to near liquid nitrogen (about 77 Kelvin, or -200 degrees Celsius), and discovered their remarkable hardness. It took them another 10 years to experiment at different temperatures, as setting up a lab and recruiting researchers who could understand what was happening at the molecular level was difficult.

Ritchie and George began experimenting with CrCoNi and another alloy that also contains manganese and iron (CrMnFeCoNi) nearly a decade ago. They created samples of the alloy, then cooled the material to near liquid nitrogen (-200 degrees Celsius) and discovered its impressive strength and durability. It took them another 10 years to continue experimenting at various temperatures of liquid helium because of the difficulty of finding a lab that could pressure test samples in a clean environment and recruiting a team with the tools and experience to analyze what was happening in the material at the molecular level.

Using neutron diffraction, electron backscattering, and electron transmission microscopy techniques, Ritchie, George, and colleagues at the Berkeley Lab, the University of Bristol, the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, and the University of New South Wales examined the crystal lattice structure of CrCoNi samples that had fractured at room temperature and -253°C. The images and atomic maps from these techniques revealed that the alloy's hardness is due to a trio of dislocation hindrances that act in a specific sequence when a force is applied to the material. The CrMnFeCoNi alloy was also tested at -253°C and performed impressively, but not as hard as the CrCoNi alloy.

Now that researchers have a better understanding of the inner workings of CrCoNi, this alloy and other HEAs are moving closer to being used in special cases. While these materials are expensive to create, they could find applications in environments where harsh environments would destroy conventional metal alloys, such as the frigid temperatures of deep space.

- Diamond is not the hardest material on Earth

- Sea slugs can be the hardest biological material in the world

- New aluminum alloy fabrication withstands 400 degrees Celsius

- Inventing hard sponge-like material 10 times more than steel

- Alloys 'transformed' 10 million types

- Invented a new super elastic alloy

- Discover the secret of the planet's hardest material, harder than diamond

- The first time to create glass alloy

- Video: People with the hardest legs on the earth

- Diamonds are about to lose the title of

- The hardest materials on the planet

- Look at the darkest material on Earth

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why?

The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why? History of the iron

History of the iron What is alum?

What is alum?