Challenges to the theory of species origins

New evidence discovered by oceanographers is a challenge for one of the oldest theories about the evolution of marine animals.

Most scientists believe that the formation of another species in the distribution area, different species formed from ancestral species only after those species become completely isolated, is the main species formation on land. and under the sea. The key to this theory is the existence of a number of natural barriers that prevent breeding between animal groups and so over a certain period of time, these animal parts become separate species.

For example, sparrows are blown by storms from South America to the Galapagos Islands (studied by Charles Darwin) completely isolated from other finches and evolved separately into different species.

Research by Dr. Dr Philip Sexton of the National Oceanographic Center, Southampton (currently working at Scripps, San Diego Oceanographic Institute) and Dr. Richard Norris (also working at Scripps) shows, style This species formation is uncommon for marine species as for land-dwelling organisms. They insist that this species formation is indeed rare in the ocean world.

The sea is not the same everywhere, but is formed from regional water blocks that differ in temperature and salinity. There is a theory that the border between these giant masses acts as barriers to the movement of plankton, creatures that cannot swim upstream, but drift themselves along the water. . The existence of these 'barriers' has led scientists to conclude that the formation of other species in the distribution area is the main form of diversification of plankton in the sea. However, new research published in Geology magazine shows a completely different picture.

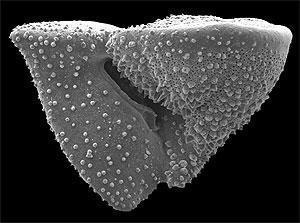

Sexton and Norris examined fossil samples of Truncorotalia truncatulinoides (a parachute species and part of a group called 'foraminifera') buried in sediments beneath the seabed. By observing the different layers of sediments in the world that contain these fossils, they can track the development of this species from their origin to the current distribution.

New evidence discovered by oceanographers is a challenge for one of the oldest theories about the evolution of marine animals. (Photo: National Oceanographic Center / University of Southampton)

New evidence discovered by oceanographers is a challenge for one of the oldest theories about the evolution of marine animals. (Photo: National Oceanographic Center / University of Southampton)

Previous studies on this animal show that it appeared about 2.8 million years ago in the Pacific Southwest and appeared in other waters about 2 million years ago. According to the theory of other species formation in the distribution region, the previous decline suggests that T. truncatulinoides confinement in the Pacific Southwest within 800,000 years indicates that there is a kind of barrier (due to the flow cycle of out) has prevented their expansion.

However, careful examination of sediments at two locations in the Atlantic shows that T. truncatulinoides appeared briefly in the Atlantic about 2.5 million years ago, before disappearing. In particular, this appearance and disappearance coincides with major changes in the Earth's climate. A more thorough study of sediments reveals this species' second appearance in the Atlantic, two million years ago, through "fluctuations", each lasting for 19,000 years, corresponding to Cyclic fluctuations in Earth's orbit attached to the Ice Age.

Sexton and Norris determined that the climate and its role in determining the marine environment prevented the growth of T. truncatulinoides, rather than the emergence of natural barriers. In this new perspective, zooplankton can be found throughout the sea but local conditions determine whether they can survive and thrive. The same thing can be seen in coconut. Sometimes they drift into the English coast and cold temperatures prevent coconuts from sprouting and growing, but if the climate suddenly changes into subtropics, coconut trees can become familiar images on the banks. sea of England.

This new idea, arguing that there are only a few natural barriers to the distribution of zooplankton, is corroborated by genetic studies that show that the rate of gene metabolism in the sea is very high. In addition, the distribution of a large number of larger marine animals such as tuna and mollusks demonstrates that despite having areas that are preferred habitats, a small number of animals This item can be found outside their 'main territory'.These observations confirm that species distribution is dominated by habitat rather than natural barriers.

Sexton and Norris' findings reinforce the evidence for the idea of regional species formation, different species formed from an ancestral species without the emergence of natural barriers. In this type of species formation, the necessary isolation may stem from a change in time and after the reproductive process. However, until more studies provide a clearer picture of marine species formation, Sexton and Norris 'argument that regional distribution and similar processes are' type the main marine species' formation, has not yet replaced the current theories.

Sexton, Philip F. & Norris, Richard D. The distribution and biogeography of the plankton: thewidedistributionof the Truncorotalia truncatulinoides.Geology, 36 (11), 899-902 (2008).

- Human ancestors are jellyfish?

- New research challenges the origin of animals on earth

- The truth about human origin

- The law explains why sometimes we say we want to achieve something but give up a few days later

- Announcing new concussions about human origin

- Controversy 'unique' about Evolutionary theory

- Footprints of 5.7 million years in Greece challenge evolution theory

- What is chaos theory?

- Why does the new cosmic theory make Stephen Hawking angry?

- Discover our incredible alien origins ...

- 8 scientific findings prove the theory of evolution is correct

- Harmless thought, but some conspiracy theories can be deadly

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend

Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast

A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast Compare the size of shark species in the world

Compare the size of shark species in the world Strange species in Southeast Asia becomes the first marine fish species 'extinct due to humans'

Strange species in Southeast Asia becomes the first marine fish species 'extinct due to humans'  Ancient humans may still live on Indonesia's Flores island

Ancient humans may still live on Indonesia's Flores island  The 'dragon' species that was thought to only exist in myths is one of the rarest on the planet.

The 'dragon' species that was thought to only exist in myths is one of the rarest on the planet.  How many animals have ever existed on Earth?

How many animals have ever existed on Earth?  Treasure of Southeast Asia: Rare animal species found in only 9 countries in the world, Vietnam just received good news!

Treasure of Southeast Asia: Rare animal species found in only 9 countries in the world, Vietnam just received good news!  'Ghost humans' discovered leaving 'hybrid offspring' in 3 modern countries

'Ghost humans' discovered leaving 'hybrid offspring' in 3 modern countries