It is not the mouse that speaks in cartoons, this is a flesh-and-bone mouse that carries a version of the human gene involved in speech, a new study says.

This finding may help clarify the process of human evolution to language and speech. Rats are often used to study the effects and effects of many diseases in humans because they have many similarities to human genes.

'In the last decade or so, we have realized that mice are really similar in many ways,' said Wolfgang Enard, a member of Max-Planck Evolutionary Research Institute, co-author of the new study. said. 'The genes are basically the same and have the same mechanism of action.'

Enard and colleagues used similar genetic points to gain insights into the evolution of speech in humans.

'With this research, we came up with the idea of using mice for research not only on disease, but also on the history of human development,' Enard said.

Enard studied the differences between human genes and the genes of primates. For example, humans have replaced two amino acids (structural units of protein) on a gene called FOXP2, which is different from gibbon.

The changes in this gene have become a permanent trait after the evolved human species developed into a new species separated from gibbons. Previous studies suggest that the human gene version has been selected in our ancestors, probably because they affect important aspects of language and speech.

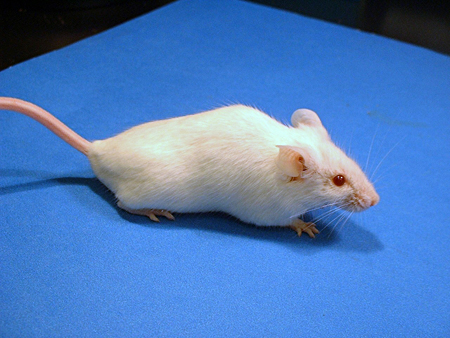

Can the mouse speak? (Photo: news-service.stanford.edu)

Can the mouse speak? (Photo: news-service.stanford.edu)

People with inactive FOXP2 genes often have a defect in their face movement time to speak, suggesting that amino acid substitutions contribute to controlling muscle movements of the tongue, lips, and larynx.

"The changes of FOXP2 appear in human evolution and one of the transformations that can lead to human speaking ability," Enard said. "The difficulty is how research is changed. This is in terms of functionality. '

This is exactly what the research team plans to do on the mouse.

The researchers replaced the human gene into the mouse's FOXP2 genes. Of course, then mice with human FOXP2 genes could not babble like babies, but they had brain circumference changes that are thought to be related to human speech. When pulled out of the mother's nest, the pups are replaced with genes that emit different sounds than the normal pups in the same case. However, Enard notes, we do not yet have enough understanding of communication in mice to be able to explain the meaning of these other modifications.

The research results are described in detail in Cell issue on 29/5. Further research is needed to determine the exact effects of these genes and the implications of these effects on differences between humans and gibbons.

'Currently, we can only speculate on the role of these influences in human evolution,' the researchers wrote.

Another study published in PloS Biology published a complete mouse genome sequence and found that there were more differences between mice and humans than previously thought. The study shows that 1/5 of the mouse genes are new versions that have appeared in the past 90 million years in the history of this species.

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why?

The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why? History of the iron

History of the iron What is alum?

What is alum?