Grasshoppers stuck 128 years in Van Gogh paintings

Experts discovered a grasshopper lacked belly and chest in the painting "Olive trees".

Managers at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, USA, found the body of a grasshopper jammed in the work of "Olive trees" arose 128 years ago by the artist Vincent Van Gogh, Telegraph on 7 November. reported.

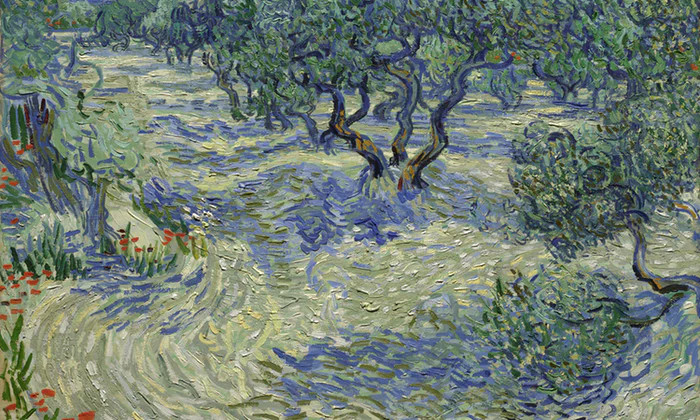

The work "Olive trees" by famous artist Van Gogh.(Photo: Guardian).

Van Gogh is famous as a proponent of outdoor painting style. Therefore, experts believe that grasshoppers have accidentally become part of the picture when he is working outside.

"Van Gogh works outdoors. He has to deal with issues like wind, dust, grass, trees, flies and grasshoppers," Julián Zugazagoitia, director of the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum, told Kansas City Star. .

The grasshopper was discovered by Mary Schafer, who preserved the paintings in the museum while examining the picture through a microscope. The animal is hidden between the brown and green markings on the painting. At first, she thought it was just a leaf.

"Finding such things in paintings is not too strange. But the discovery of grasshoppers connects people to enjoy painting with Van Gogh's painting style and the moment he created the work , " Schafer told Architectural. Digest.

Grasshoppers stick between colors.(Photo: Guardian).

In 1885, Van Gogh wrote about the outdoor painting process and the challenges he encountered in a letter to his brother, According to Van Gogh.

"Enough of the following things happen. You have to pick up hundreds of flies or more from the 4 pictures you are about to receive, not to mention dust and sand. When a person brings the paintings through the heather and the rows fencing trees for a few hours, a couple of branches were scraping through them , " he wrote.

Because the grasshopper lacks belly, chest, and no signs of movement in the picture, it may have died when it fell into it, according to Michael Engel, an insectologist who specializes in paleontology at the University of Kansas.

- Van Gogh's paintings were discolored because of ultraviolet rays

- Admire Van Gogh's extremely rare sketches

- Mysterious sunflowers in Van Gogh paintings

- Using Van Gogh's 3D printers with human tissue

- Van Gogh's painting is reproduced by 3D technology

- Disease of the great man

- Find out how to save Van Gogh's paintings

- Israeli army blocked

- Controversy around the episodes of Van Gogh's painting

- New hypothesis about the mysterious death of Van Gogh's artist

- 'Grasshopper Clouds' rises in the Middle East

- Discovering a new 'G' work by Van Gogh

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times

'Fine laughs' - Scary and painful torture in ancient times The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why?

The sequence of numbers 142857 of the Egyptian pyramids is known as the strangest number in the world - Why? History of the iron

History of the iron What is alum?

What is alum? Red hot lava flowing on snow causes confusion

Red hot lava flowing on snow causes confusion  He was awarded the title of professor at the age of 30, the youngest director in the history of Vietnamese science!

He was awarded the title of professor at the age of 30, the youngest director in the history of Vietnamese science!  Van Gogh's paintings contain surprisingly accurate physics knowledge.

Van Gogh's paintings contain surprisingly accurate physics knowledge.  Waterspout swept away ships and boats in Khanh Hoa sea

Waterspout swept away ships and boats in Khanh Hoa sea  Unexpectedly discovered Van Gogh's portrait hidden behind the painting for more than 100 years

Unexpectedly discovered Van Gogh's portrait hidden behind the painting for more than 100 years  Dolphins 'dance' in front of a fisherman's boat in Khanh Hoa waters

Dolphins 'dance' in front of a fisherman's boat in Khanh Hoa waters