Scientists found cancer cells like fat

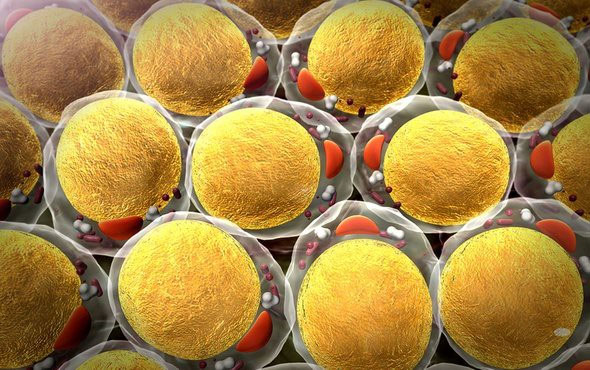

More than half of cancer cells in metastatic experiments reach locations near fat tissue.

In fact, fat contains more energy than any other nutrient. So it's not surprising that some cancer cells like to nest and grow inside fat-rich tissues.

According to a new study by scientists at the Sloan Kettering Institute (SKI), melanoma cells are one of them, they love to eat lipids every time they get a chance. Scientists have observed melanoma cells that tend to spread to near fat-rich tissues.

"This is the hypothesis that particles and soil [explain the priority of metastatic directions of cancer cells to specific organs]," said Dr. Richard White, the lead researcher. "Tumor cells like to go to fertile places. Based on our results, we think that fat tissue can be fertile soil for melanoma."

This new finding continues to reveal the relationship between overweight, obesity and cancer risk. It can also open up new therapeutic directions, interfering with the use of fat cells of cancer cells.

Scientists discovered fat tissue as "fertile soil" for cancer development.

Cancer cells like fat

Dr. White accidentally discovered the link between fat and cancer, while using seahorses to study skin cancer models. Freshwater seahorses that develop melanoma are very similar to humans. And their transparent bodies allow scientists to easily track the pathways of cancer cells and tumors as they grow.

"We have observed screening to see what factors help melanoma cells grow in some locations , " Dr. White said. "When we looked at the differences in melanocytes growing at metastatic sites, we found a lot of changes in fat-controlled cell genes."

This finding raises more questions. Do cancer cells make their own fat? Or have they eaten fat from nearby adipocytes ?

To investigate, postdoctoral researcher Maomao Zhang marked lipid in fat cells with fluorescence. She then placed the fat cells and melanoma cells into the same plate and monitored their movements.

The results clearly show melanoma cells that consume lipids.

The same phenomenon also occurs on seahorses. When Zhang injected melanoma cells next to the seahorses' fat cells, they also accumulated fat. Moreover, when melanoma cells metastasize to form new tumors, more than half metastasize to locations near fat cells.

To further test the hypothesis, the researchers collected and examined melanoma cells of MSK-treated patients. And like in seahorses, human cancer cells also accumulate fat.

Dr. Richard White, the team leader at SKI.

The fertile land for cancer develops

Further research on the relationship, scientists found that fat consumption changed the behavior of cancer cells.

Melanoma cells that eat fat have the ability to penetrate collagen and cell membranes, making them easier to spread. They also regulate metabolism, burn fat for energy instead of sugar.

Since then, scientists have raised a question: Does preventing cancer cells from consuming fat make them less aggressive?

To test this hypothesis, they used a drug to prevent FATP, a protein that allows cancer cells to absorb fat. Cancer cells have more of these proteins than normal cells, so they are more sensitive to drugs.

As expected, the reduction of cancer cell fat consumption has slowed their growth and spread.

Dr. White said the results could lead to a new treatment regimen against melanoma. They can screen for fat-sensitive cancer patients, then find an approach to prevent cancer cells from using fat to grow.

Preventing melanoma cells from exploiting fat from adipocytes can slow their growth.

Obesity and cancer

Scientists have long discovered that obesity is a factor that significantly increases the risk of cancer . Until now, they are still investigating that relationship.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization (WHO), says there are at least 10 types of cancers related to fat and overweight including: bowel cancer , esophagus, stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, uterus, ovary, kidney and breast cancer.

With every 11 cm increase in waist circumference, the risk of developing a fat-related cancer group also increased by 13%.

Now, Dr. White's research has confirmed one of the mechanisms of fat that promotes cancer development, namely melanoma.

But do other cancer cells respond similarly to fat? And what will these findings lead to in the diet? Those are still open questions that need to be studied further.

- Detects aging-causing substances in cancer cells

- Russian and Swedish scientists have found a way to kill cancer cells

- Singapore found a mechanism to make cancer cells 'suicide'

- Image of cancer cells under a microscope

- Technology causes cancer cells to destroy themselves

- Cats may be the cause of cancer

- Scientists have successfully turned breast cancer cells into ... fat

- Scientists have a safer way to treat cancer than chemotherapy and radiation

- Scientists accidentally found a cure for cancer

- Scientists are about to bring cancer cells into space to destroy them

- New discovery of metastatic mechanism of cancer cells

- Cancer drugs from proteins found in human milk

Why is Australia the country with the highest cancer rate in the world while Vietnam ranks 100th?

Why is Australia the country with the highest cancer rate in the world while Vietnam ranks 100th? New drug causes cancer to 'starve'

New drug causes cancer to 'starve' Common cancers in men

Common cancers in men America's incredible discovery: The most feared cancer cell is love

America's incredible discovery: The most feared cancer cell is love