The explosion helps measure the deepest point on the ocean floor

A scientific instrument collapsed into the sea, giving researchers the opportunity to accurately calculate the depth of the Challenger Deep.

Sitting aboard the RV Falkor in December 2014, David Barclay heard sound coming through headphones attached to the underwater receiver at the top of the ship. His mind flashed images of two scientific instruments sinking slowly into the water, falling into the Challenger abyss in the Pacific Ocean. This site is located nearly 11km below the waves, more than 1.6km above the height of Mount Everest, considered the deepest point in the ocean.

The two devices are part of Barclay's research to create a compact and low-cost method for recording the sounds of nature underwater, a project he has been working on since he was a graduate student at the Institute of Oceanography. learn Scripps. Studying the sounds of the sea not only helps scientists understand the structure of the ocean, but also helps capture many special tunes from whales or submarines. As expected, the round trip of the instrument duo to record inside the Challenger abyss will last about 9 hours. But when time ended, only one device returned from the deep sea.

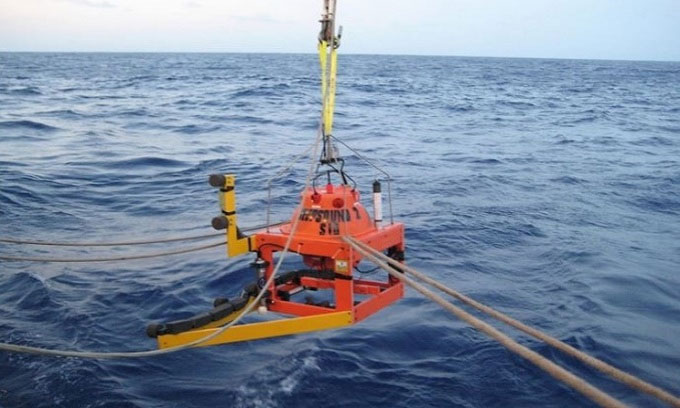

The Deep Sound Mark II device is dropped into the water.

As Barclay later deduced, the pop came from the explosion of the glass shell protecting the device, the 38cm-wide sphere that covered the electronics. Although the device was destroyed, Barclay and his team found useful sounds from the noise of the crash. The team used echoes from the explosion recorded by the other instrument to make one of the most accurate calculations of the Challenger abyss. Previous measurements have mostly fallen between 10,900 - 10,950m, but the new estimate of the depth of the Challenger abyss is 10,983m.

Scientists have long known that the Challenger abyss is the deepest point in the ocean, but it took decades to determine its location and depth. Barclay, now an associate professor at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, prepares meticulously for every expedition. On the eve of each major equipment deployment, he catalogs every possible problem. Listing possible failures helps Barclay avoid man-made disasters like forgetting to charge the battery or forgetting to turn on the device. However, there was always something beyond Barclay's control. Exploring the deepest place on the planet is no easy task. The depth of kilometers creates tremendous pressure. The pressure at the Challenger abyss is up to 1,260 kg/cm2, about 1,000 times the pressure at the water surface.

Only a few people have ever visited the Challenger abyss. The first were Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and US Navy lieutenant Don Walsh, using the submarine probe Trieste on January 23, 1960. As the Trieste neared the seabed, the temperature plummeted, cracking windows made from organic aquatic plants, creating cracks along the cramped cabin. But the windows still held up, and Piccard and Walsh made it to the safety of the Challenger abyss, lingering for 20 minutes before emerging.

Other scientists have sent remote-controlled vehicles to this abyss or measured the depth from the water's surface using sound waves. Barclay's two devices are programmed to descend to a certain depth and stay there, recording the sound of the ocean, and then return to the water. One of the two devices, called Deep Sound Mark II, will dive to a depth of 9,000m. The other device, the Deep Sound Mark III, will approach the seabed. But when the device duo disappeared from sight, there was little way to track their journeys.

Having prepared in advance, Barclay set up an underwater receiver on board to record at sea, listening for clues about what was going on below. That's when he heard an explosion. That afternoon, although not sure what happened, Barclay and his team were still observing the sea at the scheduled time to recover the equipment. They found only a device floating in the waves. The scientists towed the Deep Sound Mark II on board and listened to the audio recordings. A series of noises resounded in the still air, the noise of the Mark III's underwater explosion. Barclay speculates that one of the device's small ceramic pillars could be damaged, leading to the problem.

As the Mark III's glass shell shatters under the weight of 8km of water, the device releases an air pocket that fluctuates due to pressure before bursting into a film of tiny bubbles. The sound from the whole process travels through the sea, up to the surface before echoing back into the deep sea, where the Mark II is recording.

Measuring sonar is one of the most popular ways to map the seafloor, much like bats use echolocation to navigate the dark. For years, researchers detonated landmines near the surface of the water to produce sounds that reached the seafloor. More recently, they've turned to controlled acoustics like compressed air, says Mark Rognstad, an expert in mapping the seafloor at the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology.

Rognstad says the breakdown of the glass shell under pressure can be quite violent. Mark III's explosion was so powerful that it caused the sound waves to travel back and forth between the surface of the water and the seabed. Based on the acoustic characteristics of the echo, the team determined the arrival time of the initial bang and each echo. They then modeled the path of the sound waves, adjusting for changes in the speed of sound at different depths caused by temperature, pressure and salinity. This helped them calculate the depth of the Challenger abyss at 10,983 meters with an error of about 6 meters.

Different methods produce different numbers for the depth of the Challenger abyss. As technology advances, efforts to find the deepest points in the ocean continue. An analysis published last year derived a depth of 10,935 meters from sonar and pressure data collected during the many dives of explorer Victor Vescovo in the Limiting Factor submarine.

The explosion itself is an example of a serendipitous discovery, producing data that researchers had not expected. For their plan to listen to the sounds of nature in the Challenger abyss, Barclay and his team accomplished the goal. In 2021, they landed an instrument at the deepest point on the planet, recording the peaceful sound of the ocean for 4 hours.

- 10 things you probably didn't know about the deepest ocean in the world

- How do we measure the deepest places on Earth?

- This submarine will take you to the deepest part of the ocean!

- Shoot the deepest volcanic explosion in the sea

- Detect tremors in the deepest ocean

- Explore the ocean

- The first one to conquer the deepest point in every ocean

- The deepest point in the world on land

- Video: The scenery on the ocean floor if the water is dry

- Inside the explorer ship, the deepest part of the Earth

- Biggest underwater walker and deepest dive in the world

- The 10 most shocking mysteries of the ocean floor

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors

Surprised: Fish that live in the dark ocean still see colors Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend

Japan suddenly caught the creature that caused the earthquake in the legend A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast

A series of gray whale carcasses washed ashore on California's coast Compare the size of shark species in the world

Compare the size of shark species in the world