The world's largest frozen animal bank

San Diego's frozen zoo has just four researchers in charge of caring for more than 11,000 specimens, representing 1,300 different species and subspecies.

In a basement laboratory adjacent to a 728.4-hectare wildlife park in San Diego, California, Marlys Houck looked up to see a man in uniform holding a blue insulated bag containing parts. eyes, trachea, feet and feathers. The bag includes small pieces of soft tissue collected from animals that died naturally at the zoo.

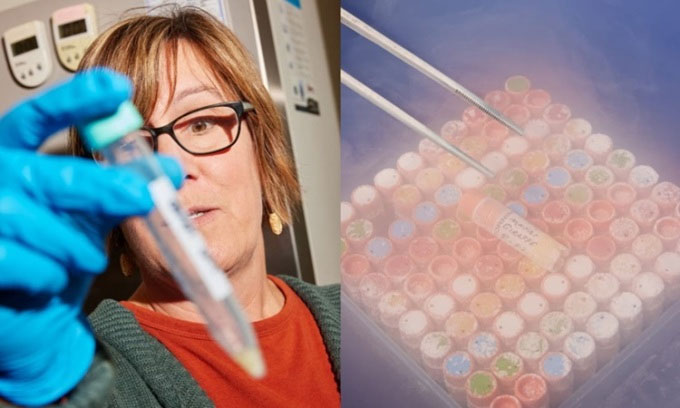

Research coordinator Ann Misuraca takes the cell container out of the incubator to examine it under a microscope at the Frozen Zoo. Photo: Maggie Shannon

The person holding the bag was volunteer James Boggeln. He gave it to Houck, the manager of a laboratory called "Frozen Zoo". She and her colleagues will begin the process of banking tissue samples for research and preservation for the future. They placed the tissues in flasks to let enzymes digest them, then lab staff slowly incubated them for a month, growing a large number of cells that could be frozen and reactivated for later use, according to the Guardian .

At nearly 50 years old , the Frozen Zoo contains the world's largest and richest collection of ancient living cell cultures with more than 11,000 specimens, representing 1,300 different species and subspecies, including 3 Species are extinct and many species are about to become extinct. Today, the Frozen Zoo is run by a team of four female employees. They oversee a vast collection of test tubes labeled as "giraffe", "rhino" and "apustrine", all stored in large circular tanks filled with liquid nitrogen. In a world plagued by climate and biodiversity crises, freezing species offers a way to preserve them for the future.

The work here is meaningful, but the accelerating extinction crisis puts pressure on Houck and his colleagues. It's a race against time to get specimens into the Frozen Zoo before the animals disappear from the outside world. The work is meticulous because all specimens from birds, mammals, amphibians and fish require different processing. Houck clearly felt the pressure in her position. When her predecessor was still in office, a technical incident caused the loss of 300 samples and a year's worth of work. Therefore, Houck devoted all his attention to protecting the safety of frozen specimens at the zoo.

Manager Marlys Houck and Misuraca remove specimens from the nitrogen tank. (Photo: Maggie Shannon)

The zoo was founded by a German and American pathologist named Kurt Benirschke in 1972. Benirschke began his collection of animal skin specimens in a laboratory at the University of California, San Diego, and moved it to the zoo. San Diego after a few years. At that time, there was no technology that needed to use such specimens beyond basic chromosome research.

At the frozen zoo, Houck took a test tube from the liquid nitrogen tank. These storage tanks are pressurized at -196 degrees Celsius, a temperature that prevents cells from moving or changing, maintaining them in a state of suspended animation. From this temperature, cells can revive and continue to live after decades or centuries.

No two species are identical, some animal groups are more difficult to conserve than others. The frozen zoo started with mammals, then expanded to birds, reptiles and amphibians. The success rate with mammals is up to 99%, according to Houck. With amphibians, the success rate is 20 - 25%. Each rack in the liquid nitrogen tank contains 100 test tubes, each tube containing 1 - 3 million living cells. Such cells could provide viable solutions to a wide range of current and future problems.

Ultimately, cells could be used to bring back completely extinct species, but that is not the main purpose. Instead, the material is used to save species that are difficult to survive today. In 2020, Frozen Zoo used cryogenically preserved DNA to clone a black-footed ferret, the first endangered species in the US to be cloned. Last year, cells frozen and preserved 42 years ago were used to clone two critically endangered Przewalski's wild horses, bringing valuable genetic diversity to the living horse population to increase their ability to fight disease. new and threatening from the environment.

The work at San Diego's Frozen Zoo is part of a global effort to cryogenically preserve everything from animals to seeds . Today, there are dozens of cryogenic banks around the world, mainly located in North America and Europe. The work at the San Diego lab is particularly groundbreaking, according to Sue Walker, scientific director at Chester Zoo. She said that within a few decades, researchers will transform living cells into pluripotent stem cells, which can be reprogrammed to create eggs and sperm.

Obtaining permits to collect animal tissue in many other countries is quite difficult, so researchers hope to increase the productivity of local collection, especially near conservation centers in Africa, South America and the East. South Asia. The research team adds about 250 - 300 specimens to the zoo each year. The nitrogen tank room is full, but the tanks are not at capacity, so lab members continue to culture and preserve cells that will determine the future survival of endangered animals.

- Russia set up an DNA bank of all species

- Rice is safely preserved in Philippine gene bank

- Future sperm bank on the Moon

- Discover Britain's largest brain bank

- The process of turning human brain into immortality in America

- Roll out the outstanding frozen mummification in the world

- Switzerland: Hackers cheat 1.1 million USD

- Half a million people will join the Bio Bank

- Cost $ 90,000 to be frozen in Australia

- Making dog's DNA bank

- FBI builds the world's largest bio-data bank

- Sperm bank denies red hair

Norway built the world's tallest wooden tower

Norway built the world's tallest wooden tower Kremlin

Kremlin Ashurbanipal: The oldest royal library in the world

Ashurbanipal: The oldest royal library in the world Decoding the thousand-year construction of Qin Shihuang shocked the world

Decoding the thousand-year construction of Qin Shihuang shocked the world