The secret room reveals the hidden corner of the Iron Age

An unexpected discovery reveals ancient artwork that was once part of an Iron Age complex beneath a house in southeastern Turkey. This unfinished work is depicting a divine procession, along with the meeting of different cultures.

Originally in 2017, thieves broke into the underground complex by punching a hole in the ground floor of a two-story house in the village of Başbük. The hole was punched into the limestone foundation, about 30 meters below the house.

As the thieves were apprehended by authorities, in 2018 a team of archaeologists carried out a rescue excavation of the underground complex before it was further eroded in the fall to study the extent of the damage. importance of this area and the art on rock slabs. What the researchers found was shared in a study published Tuesday by the journal Antiquity.

The artwork was born in the 9th century BC during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which began in Mesopotamia and gradually expanded to become the greatest superpower at the time. Between 600 and 900 BC, it extended to Anatolia - a large peninsula in Western Asia that included most of present-day Turkey.

Archaeologists followed a long stone staircase to an underground room, where they found rare works of art on the walls.

"As the Assyrian Empire exercised political power in Southeast Anatolia, the Assyrian governors showed up," said study author Selim Ferruh Adali, an associate professor of history at Ankara University of Social Sciences in Turkey. their power through Assyrian court art". A good example of this style is the carving of monumental stone reliefs, the study authors write, but examples of the Neo-Assyrian Empire are rare.

Mix of cultures

The work shows cultural integration instead of outright aggression. The names of the gods are written in the local Aramaic language. Icons representing religious themes from Syria and Anatolia created in Assyrian style.

"It shows that during the early period of Neo-Assyrian rule, there was the coexistence of Assyrians and Arameans in the same area," says Adali. "The village of Başbük provides scholars studying the nature of empires with an outstanding example of regional traditions, ways to maintain voice and, importantly, the exercise of imperial power," says Adali. expressed through the art of figurative carving".

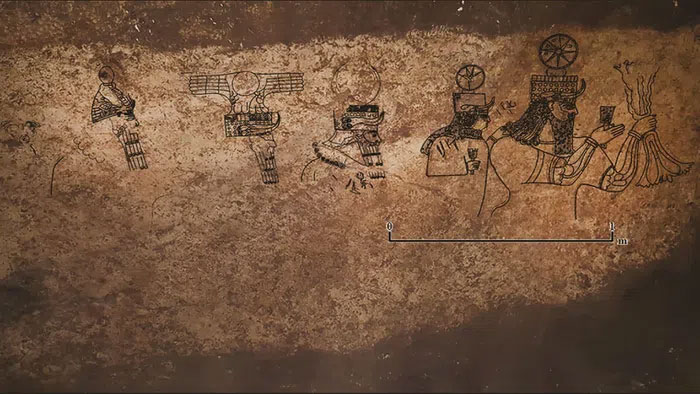

Adali shared: "The artwork showing the eight gods is not finished yet. The largest figure is 1.1 meters high. Local deities in the artwork include: Moon God Sîn, the Storm God Hadad, and the Goddess Atargatis. Behind them, the researchers identified a sun god and other deities. The lines of description combine symbols of the Syro-Anatolian religion with representative elements of Assyria".

Part of the artwork features the Storm God Hadad and Atargatis - the goddess of northern Syria.

Adali said: 'Bringing Syro-Anatolian religious themes to illustrate Neo-Assyrian Empire features in a way one would not expect from previous findings. "They reflect an earlier period of Assyrian arrival in the area when the local environment was more prominent."

Upon discovering this artwork, study author Mehmet Önal - professor of archeology at Harran University, Turkey said: "When the dim light of the lamp shines on the images of the gods, I trembled with fear when I realized I was facing Hadad's expressive eyes and majestic face."

The mystery is open

The team also identified an inscription that may indicate the name of Mukīn-abūa, a Neo-Assyrian official who served during the reign of Adad-nirari III from 783 to 811 BC. Archaeologists suspect he was sent to the area at the time and was using the complex as a way to appeal to locals.

But the unfinished structure and they remained unfinished all this time suggests that something was up with the builders and artists to abandon it, it could even be an uprising.

'The work was done by local artists serving the Assyrian government, who adapted Neo-Assyrian art into a provincial governance context,' says Adali. It is used to perform ceremonies overseen by the provincial government. It may have been left unfinished due to changes in provincial government and practices, or as a result of political-military conflicts."

Adali is the inscriptionist of a group of people who read and translated the Aramaic inscriptions in 2019 using photographs taken by the team, who had to work quickly to study the site. .

Adali said: 'I was shocked when I saw the Aramaic inscriptions on such works of art, there was a feeling of great excitement overwhelming me when I read the names of the gods.

The complex was closed after excavations in 2018 because it was no longer stable and in danger of collapsing. It is currently under the legal protection of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archaeologists are eager to resume their work if excavations can proceed safely again. They can capture new images of artwork and inscriptions, and can discover more artworks and artifacts.

- Discover the secret passage in the British Parliament leading into historical treasures

- The skeptical expert went to the secret room hidden in King Tut's tomb

- Hidden behind every famous building is a secret not everyone knows

- Secretly 'heavenly' without any hotel staff daring to tell you

- Discover the mysterious room inside the underground palace of Roman tyrants

- Decipher the secret room of medieval priests

- Video: Airship robot explores the hidden room in the Great Pyramid

- Photographing a self-portrait in a French museum, an expert discovers a secret that has been hidden for 160 years

- QZ8501 suffered from the phenomenon of

- Why iron is rusty?

- Discover the mysterious iron chest in the 'treasure city' of Canada

- The hidden room in the Great Pyramid may contain the pharaoh's throne

Discovered an ancient centipede fossil 99 million years old

Discovered an ancient centipede fossil 99 million years old Discovered bat-like dinosaurs in China

Discovered bat-like dinosaurs in China Discovered a 200-year-old bronze cannon of the coast

Discovered a 200-year-old bronze cannon of the coast Discover 305 million-year-old spider fossils

Discover 305 million-year-old spider fossils