Why did the Tonga volcano produce record amounts of lightning?

The undersea Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano produces unprecedented amounts of lightning, accompanied by explosions that can be heard from thousands of kilometers away.

Just a few weeks ago, an undersea volcano recognizable through two uninhabited islands in the Kingdom of Tonga began erupting. At first, the eruption seemed innocuous, with columns of ash and small tremors that very few people living outside the archipelago would notice. But within 24 hours, the volcano named Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai captured the world's attention.

After a period of calm in early January 2021, the eruption became increasingly intense. The middle part of the island disappeared in the satellite image. The towering ash columns attract a record amount of lightning. According to Chris Vagasky, meteorologist and lightning applications manager at the Vaisala weather measurement company in Finland, 5,000 to 6,000 lightning bolts strike the volcano every minute.

In the early morning of January 15, the volcano experienced a powerful explosion. The shock wave spreads out from the island at the speed of sound. People in some parts of New Zealand more than 2,090 km away can hear sonic booms. The shock wave travels halfway around the world, reaching as far as England at a distance of 16,093km.

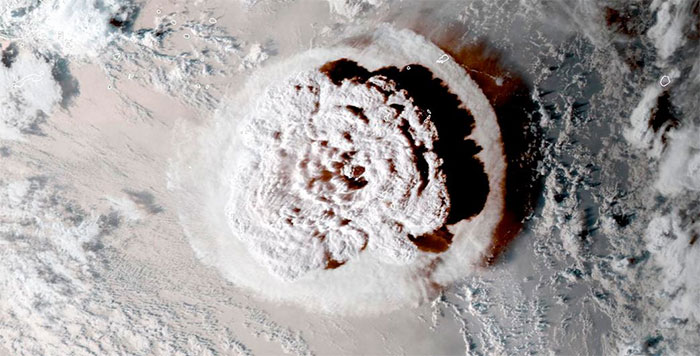

An undersea volcanic eruption in Tonga on January 15.

The tsunami quickly hit the people in panic. The tsunami hit Tongatapu, the kingdom's main island, where the capital Nuku'alofa is located, just a few dozen kilometers south of the volcano. Streets flooded and people rushed to evacuate, disrupting communication networks. Waves gliding across the northwest Pacific Ocean, creating surges in Alaska, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Stations in California, Mexico, and parts of South America also recorded small tsunamis.

Recent research into the geological history of volcanoes shows that sudden powerful eruptions like this are relatively rare. Every few thousand years there is an eruption of similar magnitude. For Tonga, it was a devastating disaster, said Janine Krippner, a volcanologist with the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcano Program. Scientists are anxious to find out what caused the eruption and what happened next. But information appeared very slowly, partly because the volcano was far away and difficult to see up close. Researchers are learning about the tectonic and geological factors involved in the eruption, thereby predicting the future of the volcano.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai is located in the South Pacific region, where many volcanoes are concentrated. Some volcanoes rise above the water while some are submerged deep under the water. Past eruptions created pumice rafts the size of a city. Many volcanoes exploded, creating new archipelagos almost immediately. This volcanic belt exists because the Pacific tectonic plate continuously plunges deep below the Australian tectonic plate. As the tectonic plate sinks deep into the superheated rock layer of the mantle, the water inside is heated and overflows into the upper mantle. Absorbing water makes the hot rock layer easier to flow. The process creates a lot of sticky and gas-filled magma, the perfect conditions for explosive eruptions.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai Volcano is no exception. The strip of land above the volcano is more than 19 km wide and has a cauldron-shaped crater about 4.8 km wide that is obscured by sea water. This crater erupted violently in 1912, sometimes rising above the waves before continuing to sink under water due to erosion. The 2014-2015 eruption created a long-lived island, home to a variety of vibrant plants and gray-backed pig owls.

When Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai started erupting again on December 19, 2021, the volcano caused a series of explosions and a 16 km high column of ash, but that's not unusual for an underground volcano, according to Sam Mitchell, a volcanologist at the University of Bristol, UK. Over the next few weeks, new lava erupted enough for the island to expand by nearly 50%. On New Year's Eve, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano becomes quiet. Then, in just two days, the situation took a sudden turn. The eruptions of the volcano began to become more intense, lightning appeared from the ash column more than any other eruption in history.

Volcanoes can produce lightning because ash particles in a column of smoke collide with each other or with ice in the atmosphere, creating an electrical charge and producing lightning. Since its inception, lightning from the Tonga eruption has been detected by Vaisala's GLD360 network. The system uses signal receivers around the globe, which can "hear" lightning in the form of powerful radio bursts. During the first two weeks, the system recorded a few hundred to several thousand lightning flashes per day. That is nothing out of the ordinary.

But from the evening of January 14 to the early morning of January 15, the volcano produced tens of thousands of lightning bolts. At one point, the volcano in Tonga produced 200,000 lightning bolts in just one hour. Compared to Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai, the 2018 eruption of Anak Krakatau volcano in Indonesia produced 340,000 lightning bolts in a week.

The scene can be amazing from a distance, but from a distance, the scene looks like the apocalypse, with thunderous lightning crashing down, buffered by endless rumbling thunder and boiling volcanoes. Many lightning bolts hit the land and sea. Why did the eruption produce such a record amount of lightning?

The presence of water always increases the risk of lightning, says Kathleen McKee, a volcanologist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. When magma mixes with water, the water is heated and intensely vaporized, blasting the magma into millions of tiny pieces. The more and finer the particles, the greater the number of lightning bolts.

The heat of the eruption also caused water vapor to rise to a higher, colder atmosphere. There, the water vapor turns into ice, says Corrado Cimarelli, an experimental volcanologist at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. That process provides more particles for the ash column to collide and generate electricity. But researchers can't pinpoint exactly why the Tonga eruption generated the current record amount of lightning because the volcano is located so far away, Cimarelli said.

Massive amounts of lightning aren't the only "prelude" to a volcanic disaster. On the morning of January 15, satellite images revealed that the island was no longer developed. The middle part of the volcanic island disappeared. When the giant explosion occurred, the shock wave traveled across the globe at breakneck speed, followed by a tsunami that swept over several islands in the Tonga archipelago before moving across the Pacific Ocean.

Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, a seismologist and volcanologist at Western Washington University at Bellingham, said the explosion occurred with incredible energy. But currently there is not enough data to draw definite conclusions about the cause of the tsunami. Tsunamis occur when large amounts of water are displaced, due to an underwater explosion, a lot of rock suddenly comes out of a volcano and falls into the sea, or a combination of both and many other factors.

With the ash column obscuring the volcano and most of the volcano submerged, scientists still need more time to gather indirect data before drawing conclusions. Clues could come from the variety of sound waves the explosion emitted or the redistribution of mass around the volcano.

The massive explosion and powerful tsunami from the relatively small volcanic archipelago reveal the incredible power of the eruption. Although not the cause of the tsunami, the shock wave caused another large wave. Fast-moving air hits the ocean surface hard enough to push water out in a phenomenon known as a gas tsunami.

Shane Cronin, a volcanologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, said the clues to the cause of the violent eruption could lie in the chemical composition of the volcano, which changes as the magma inside in evolution over time. Like many other volcanoes, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai must re-fill the magma reservoir before another powerful eruption occurs.

Currently, volcanologists are actively studying the eruption in Tonga to increase understanding of similar events in the future and work to minimize damage.

- Lightning flashed on the erupting crater in Japan

- Record of 700km of lightning

- Impressive moment with nature's

- Indonesia's volcano shot itself

- Children's remains are placed on top of a volcano to withstand lightning strikes

- Terrifying spectacle when lightning hit ... volcano

- China: The record of 141 people died from lightning

- Saturn lightning storm breaks the record in our solar system

- The suspect is super volcano on Mars

- After a record heat, Sydney put lightning on

- The first time recorded the mysterious volcanic thunder

- Lightning disaster

Is the magnetic North Pole shift dangerous to humanity?

Is the magnetic North Pole shift dangerous to humanity? Washington legalizes the recycling of human bodies into fertilizer

Washington legalizes the recycling of human bodies into fertilizer Lightning stone - the mysterious guest

Lightning stone - the mysterious guest Stunned by the mysterious sunset, strange appearance

Stunned by the mysterious sunset, strange appearance