Phishing Art: The truth about crystal skulls

Just three months after the Quai Branly Museum in Paris spotted a crystal skull - once hailed as a mysterious Aztec masterpiece - a fake, the British Museum and the Smithsonian Institute bitterly recognized them as well. is the victim of fake skulls.

Scientists from the two prestigious institutes stated that their crystal skulls were cut and polished with industrial age tools, not by the hands of ancient Central American craftsmen.

'The skulls under consideration do not belong to pre-Columbian times. Surely they will be considered modern products. Each skull was probably formed about a decade before they were offered for sale. '

The skulls became stars in exhibitions at all three museums long before the movie 'Indiana Jones: Kingdom of the Crystal Skull ' was released this year.

Superstitious people believe that they belong to a set of 12 skulls, capable of healing and other mysterious powers, dating back to the ancient Chinese American culture. According to an ancient story, 12 skulls assembled together with a 13th will create immense power to help prevent the earth from being overturned on December 21, 2012, according to the 'doomsday'. Mayan calendar.

The mythical devotees had a painful April 18 when Quai Branly claimed they found the perforated hole and the groove on the quartz skull about 11cm tall, showing the existence of 'jewelry grinding wheel and Other modern tools. '

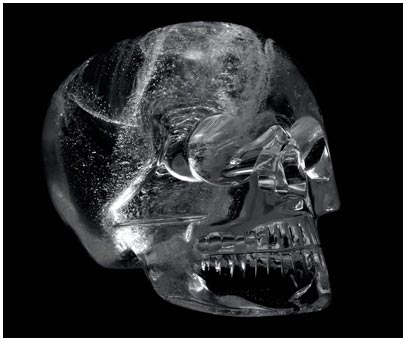

The crystal skull is displayed at the British Museum's Wellcome Trust Exhibition.The skull, originally believed to originate from this ancient Aztec civilization, was identified as a fake after investigators found traces of the rotation on the work.(Photo: static.howstuffworks.com)

Doubts also surfaced around the skulls in London and Washington, when art experts noticed they were unusually large with perfectly aligned teeth marks. To find scientific conclusions, scientists from the two museums examined the skull with an electron microscope, observed extremely small scratches and the marks left by the sharpening tool. These marks are then compared to crystal cups, crystal beads and dozens of other emerald jewelry known to have serious Aztec or Mixtec origins.

The skull purchased by the British Museum in 1987, made of transparent crystal stones and 15 cm high. The Smithsonian skull was received by the museum in 1992, made from quartz and about 25.5 cm tall.

Investigators discovered that the revolutions caused the British skull to have a sharp shape, a drill that created nostrils and eyes, and diamond or corundum attached with iron or steel tools to smooth the surface. its upper side. The American skull has a faint trace of the tool, but these vestiges are consistent with rotations or crushing pieces.

There is no evidence that the rotation was used to cut stones in Central America before Europeans arrived.

Investigators also discovered red and black in a tiny cavity of the Smithsonian skull. X-ray diffraction proved it to be silicon carbide - a hard compound that only exists naturally in celestial bodies but is common in modern industrial abrasives.

Tiny irregularities in quartz show that minerals used in London skulls originate from the European Alps, Brazil or Madagascar, while quartz in Washington's skull 'may have many sources', including Mexico and the United States.

Investigators carefully studied the archives of both museums, the Paris Museum of Humanity, the French National Library, the Latin American Community Museum and the press to find the origins of the skulls. The only document that exists for the Smithsonian skull states that it was purchased in Mexico City in 1960. Researchers believe the skull 'may be produced shortly before being bought'.

As for the skulls in the British Museum and Quai Branly, paper documents lead to a French antique collector named Eugene Boban Duverge.

Boban had a shop in Mexico City and found his way to galleries in Paris thanks to the 1863-1867 "French Intervention" , when French troops invaded Mexico. He created the 2000 pre-Columbian relics, the largest collection in Europe today. It includes several crystal skulls, including newly discovered fake items in London and Paris.

The skull in the hands of the British Museum was bought by Boban between 1878 and 1881, probably in Europe. In 1885, he tried to sell it to the Mexican National Museum, but was refused.

A year later, Boban sold it at an auction for jeweler Tiffany in New York. Two years later, Tiffany sold the skull to a California businessman. Nearly a decade later, this person went bankrupt and asked the jeweler to find a new buyer.

So the vice president of Tiffany, George Kunz, went to the British Museum.

He suggested the acquisition of 'this remarkable object', drafting the master's past, beginning with a Spanish soldier brought back from Mexico, and quoting others that the skull of ancient Mexican origin but no one is sure.

The rest, as people say, belongs to history . and human beliefs.

- Legendary legend 'Crystal skull'

- Plug-in helps detect phishing websites

- Mysterious decoding of children's skulls scattered around the lake in Switzerland

- Why do medieval women have an alien-like skull?

- Phishing website grows 166% / month

- Ancient Roman skulls under the Thames

- Mysterious skulls appear in Syria

- Damage caused by phishing established a new record

- Detecting two mysterious skulls of aliens

- Festival decorated skulls

- Doubts about the mysterious crystal skull case

- Small gold is super expensive

Discovered an ancient centipede fossil 99 million years old

Discovered an ancient centipede fossil 99 million years old Discovered bat-like dinosaurs in China

Discovered bat-like dinosaurs in China Discovered a 200-year-old bronze cannon of the coast

Discovered a 200-year-old bronze cannon of the coast Discover 305 million-year-old spider fossils

Discover 305 million-year-old spider fossils